The Brothers Grimm (Jacob and Wilhelm, btw) are generally given credit for publishing the first collection of fairy tales. I hate to quibble, but Mother Nature is the OG spinner of stories full of abandonment, alchemy, metamorphosis, maturity quests, enchanted slumbers, and awakenings. Read closely, and you’ll discover that folksy sagas don’t use forests, meadows, mountains, lakes, and rivers simply as scenery, and the creatures who live in those landscapes aren’t bit players – the natural world and how it works is woven into the very fabric of these fables.

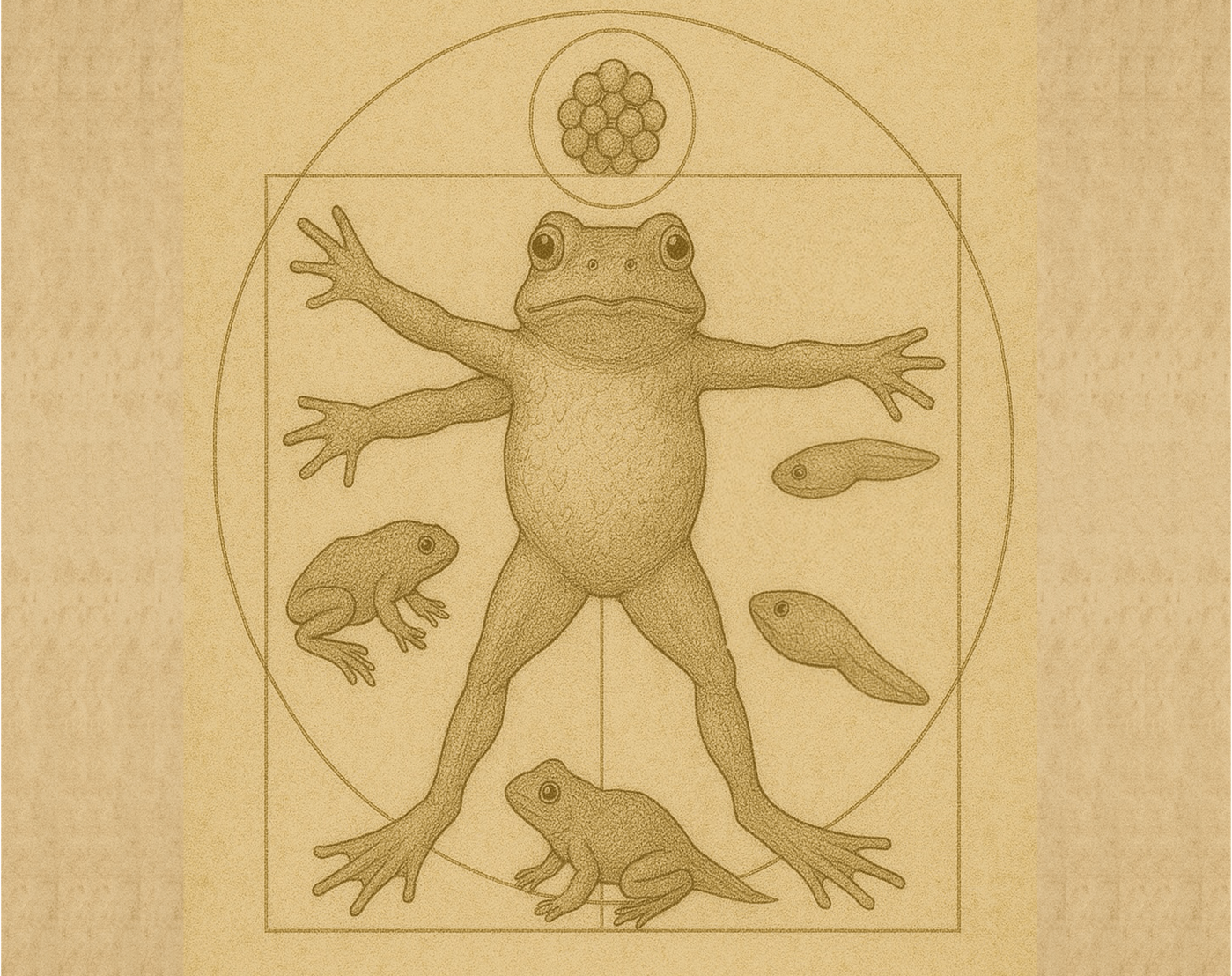

For example, before Rumpelstiltskin, the Beast, Jack Frost, Snow White, and Sleeping Beauty ever graced the pages of a book or an animated film there were shape-shifting amphibians.

Skeptical? Let me tell you a story about the American toad (Anaxyrus americanus, formerly Bufo americanus)…

This yarn begins, as so many fairy tales do, with absentee parents.

Abandonment

Once upon a time, a gal checked out a guy at the local watering hole when she heard him crooning her favorite tune. It was lust at first sight, and in short order the pair agreed to go skinny-dipping. While he gave her a big hug from behind our Mom-to-be released two gelatinous strings of 2,000-20,000 eggs into the water, and the soon-to-be Dad added his contribution.

But there’s no happily ever after for this couple. He and she hopped away after their hook-up without even a backward glance, for each other or their progeny. The proto-urchins were on their own, left behind to fend for themselves in the mean streams, ponds, and puddles of North America east of the Mississippi.

Alchemy

The brownish-black and cream eggs will hatch into tadpoles in 3-12 day, armed with gills to help them breathe under water and a tail propeller for swimming. Hard workers from the get-go, they start feeding on algae and aquatic plants, converting calories into toad like Rumpelstiltskin spinning straw into gold.

Of course, that’s assuming their water-nursery’s temperature and dissolved oxygen are just right, and that it doesn’t evaporate faster than the eggs can develop. Oh, and also assuming the eggs don’t become fish food… or a meal for dragonflies, damselflies, water beetles, salamanders, turtles, ducks, herons, egrets, kingfishers, muskrats, otters, raccoons, or other tadpoles. Some of these critters will pose a predation threat throughout a toad’s lifespan.

That said, tadpoles and toads aren’t completely defenseless. Tadpoles avoid some of their predators using the “safety in numbers” strategy, staying close to one another in formations called knots, clouds, shoals, or schools, depending on the region. They’ll also swim in very shallow water with plenty of vegetation for hiding, when that’s available. And if all else fails, toads and other amphibians will use chemical warfare against their foes.

[Don’t act surprised. This is a fairy tale. You had to know poison was bound to appear in the story at some point.]

When American toads and tadpoles feel threatened, their skin produces and secretes bufotoxins, milky alkaloid neurotoxins. Bufotoxins aren’t terribly toxic – they’re not strong enough to cause a human heroine to fall into a coma that can only be cured by a charming prince’s kiss, for example. But the poison can cause skin and eye irritation, or nausea and vomiting if ingested. And the effects can be more serious for smaller creatures, including dogs and cats.

Metamorphosis

During their underwater era, the tadpoles will undergo a dramatic, one might even say magical, transformation. Their tails become the building blocks for lungs and limbs. It’s kinda like when the Beast changes back into a prince, his horns becoming thick, wavy hair, his paws morphing into hands and feet… except that what takes about two minutes in a Disney film takes about two months in a pond or marsh, and there’s no spiral of twinkling colorful light. Unlike insects, who often duck underground or behind the curtain of a chrysalis or cocoon to deconstruct their pupal tissues and reassemble them into an adult form, toads and other amphibians do their shape-shifting in situ, visible to anyone who happens to be nearby… including, perhaps, the beautiful, bookish only daughter of an eccentric inventor.

Maturity Quest

When their metamorphosis is complete, the resulting creature bears no more resemblance to it’s previous form than a moth or butterfly resembles a caterpillar. A tadpole that measures less than a quarter-inch upon hatching (<6 mm) will grow to an adult nose-to-tail-nub length of 2.0–3.5 in (5–9 cm), or about the size of a small sprite. The world record length is 4.4 in (11.1 cm), though, which has to be the toad equivalent of a giant.

As tadpoles, these wriggling black foundlings were practically indistinguishable from one another, but as adults they’ll have a great deal of color and pattern variability, particularly among the females – anything from solid or speckled tones of yellow, buffy brown, copper, or black. Plus, their skin color can change in response to habitat, humidity, temperature, and stress, which is a pretty mythical trait, you have to admit.

The toadlets haul their tiny butts out of the aquatic nursery that’s the only home they’ve ever known, bravely clamber out of the water and head for the higher ground of nearby upland forests and grasslands. The first order of business is for the froglets, who have been swimming their wholes lives to this point, to figure out how to move on land using arms and legs. We’ve all got to crawl before we can run, or in this case, hop, and if you’ve ever watched someone try to walk after spending the day on a sailboat, you’ll have a pretty accurate mental picture of the toadlets’ first clumsy, stumbling steps onto a solid surface.

In no time at all, though, they’ll be feeding voraciously on ants, worms, slugs, centipedes, crickets, moths, spiders, and other invertebrates — a single adult toad may eat more than 10,000 insects over the course of summer. From that point forward, they’ll spend far less time in water than their froggy cousins. However, toads will go looking for a drink when the weather is too hot and dry to provide a refreshing morning dew, when they feel like having a short soak, or when puberty announces that it’s time to reproduce.

Enchanted Slumber

Fairy tales follow specific story arcs. There has to be some kind of calamity before we can move on to courtship, and for toads that means a months-long deep sleep. Slumber is induced, in this case, not by a spell from an evil stepparent (we’ve already determined that parental care of any kind is outside the norms of toad culture) but by decreasing daylight hours and a seasonal drop in the average ambient temperature.

In mid-to-late autumn, when the mercury starts hanging out around 50°F (10°C) and Jack Frost starts dropping in for visits, invertebrate food sources begin to get scarce and toads start looking for a place to dig in for the winter, often quite literally. For a toad, winter shelter can be a personally excavated or borrowed burrow 1 to 3 feet deep, depending on the frost line, an ant mound, a tree stump or log, or beneath a building foundation.

Mostly solitary hibernators, toads will tolerate close quarters when habitat is scarce, but they don’t do it to conserve body heat. That’s because when they’re dormant they don’t really have any warmth to share, and they don’t need much anyway — American toads produce a cryoprotectant that acts like antifreeze, preventing ice crystals from forming in their cells… although if the temperature is low enough to completely freeze the toad’s body then their long winter’s nap becomes eternal.

Awakenings

The vernal equinox in March serves as the Northern Hemisphere’s alarm clock, and once temperatures are consistently rising to 40°F (4°C) and above, the toads who survived will begin to stir. Unlike Sleeping Beauty and Snow White, whose eyes flutter open mid-kiss and are up, out of bed, and planning ill-considered weddings in a matter of minutes, toads take a more measured approach, waking gradually, carefully moving stiff limbs as they prepare to extricate themselves from their winter hideaway. They’ll take some time to get reacquainted with their surroundings, snack on some earthworms and crickets, and the males will start doing vocal warm-ups.

Then, once they’ve come of age in 2 or 3 years, Spring will turn a toad’s thoughts to one night stands… [hmm, better change that since we’re talking about fairy tales..] Spring will turn a toad’s thoughts to one true love. Like their parents before them, they’ll head to a nearby water feature and start swiping left or right.

The morning after they’ll go on with their lives, leaving strands of vulnerable toad eggs behind to find their own way in the world.

Same as it ever after was.

The End

Life is better with Next-Life is better with Next-Door Nature—click the “subscribe” link in the lower left-hand corner of the footer and receive notifications of new posts! Have a question about wildlife and other next-door nature? Send me an email and the answer may turn up as a future blog post.

© 2025 Next-Door Nature—no reprints without written permission from the author (I’d love for you to share my work but please ask). Thanks to the following photographers for making their work available through a Creative Commons license: Dave Spier, Vicki DeLoach, Brian Gratwicke, Emily Kloosterman, Kerry Wixted, USFWS Midwest Region, and Dani Tinker.

Leave a comment